I once received an email from a friend who asked me to tell him my understanding of God and suffering. I said:

I just put Henryk Gorecki's "Miserere" into the CD player. I love this CD, but I ration listening to it, because it is too powerful for common hours. After beginning in a barely audible whisper, so unobtrusive that it is annoying – has the music started? What are they saying? – the unaccompanied chorus begins to sound unstoppable – reverent, orderly, but unstoppable. They voice a barely perceptible drip, drip, drip that morphs into a gently lapping, and then an overwhelming, ocean wave. These singers, first a male chorus, and then women, are saints marching on their knees, but, nonetheless, marching. They repeat the same words over and over. It sounds as if they are chanting, "Make way" or "We win," but what they are really chanting, over and over, throughout the entire half-hour piece is "Domine deus noster, miserere nobis," "Lord our God, have mercy on us." This is supplication and self-mortification as power.

Gorecki wrote "Miserere" in 1981, in protest against Communists beating up on demonstrators from the Polish Peasant Party and Rural Solidarity. Gorecki knew that, since his work was a protest, it would have to bide its time before any audible performance. I was in Poland as Communism was falling – and as "Miserere" had its first hearing. As I listen, now, to Gorecki's ghostly chorus quietly, slowly, determinedly chant, rising, inevitably, to an unconquerable crescendo, I think of those gray, underfed, betrayed peasants, cleaning women, coal miners, shipyard workers, marching, inexorably, toward freedom, and their own apotheosis.

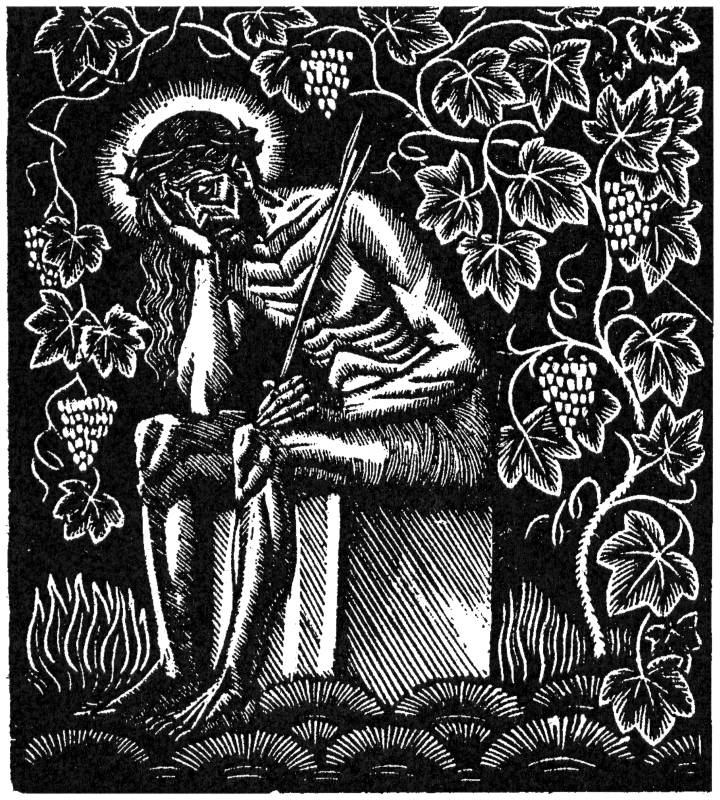

You open, "Suffering," and I raise your bet, "Poland. The Christ of Nations, a long-suffering motherland that is repeatedly invaded, and repeatedly rises up to show her invaders that the worst suffering exists only to demonstrate the best in the human spirit." Poland, land of Auschwitz. Poland, land of Irena Sendler, who endured Nazi torture rather than betray the Jewish children she had rescued. Poland, birthplace of Pope John Paul II, who had been a slave laborer for the Nazis, Lech Walesa and Adam Michnik, who, together with other former prisoners from other nations, and peacefully, took down the Soviet Empire. Without the night, we cannot recognize light.

One problem with biographies of giants like these is that they are too often exploited to silence discussion. If some middle class teenager in Ohio is so sad he wants to hang himself and he doesn't know why, invoking the nightmare of Nazism to make that kid feel that his own problems are trivial, or invoking heroism to shame that kid into feeling weak, escapes the duties assigned to those who witness suffering.

When we talk about God and suffering we need to surrender. Our contribution will not be final. Our words will be a cross-section of an ever-flowing stream. We need to go in search of answers, but compassion demands that we never conclude that we've reached the destination where the answers reside. One signature of suffering is the fresh intensity of it in each one suddenly afflicted. Suffering is being without answers, even if you have read all of the best books. If we encounter a sufferer who doesn't know anything but suffering, we need to be willing to share her fresh, new, individual hell.

Another problem is the belief that suffering always elevates. The Poles I met were so self-conscious of their own status as a crucified nation that they would broach this in conversation with me: "They say suffering makes you noble, and that you should seek it out. That is nonsense, and it is poison. We know because we see it. Suffering can destroy you. It is how you respond to the suffering that you can't avoid that makes all the difference, not the suffering itself. You should not seek it out; but you should not run away from a goal if you must endure suffering to achieve it."

Thanks to the miracle of the internet, I was able to find, in seconds, the very first article I ever read that introduced me to Gorecki. It was in TIME magazine and it's linked, below.

ReplyDeleteI remember the line about drivers pulling to the sides of roads, they were so enraptured by his "Symphony of Sorrowful Songs."

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,977932-1,00.html