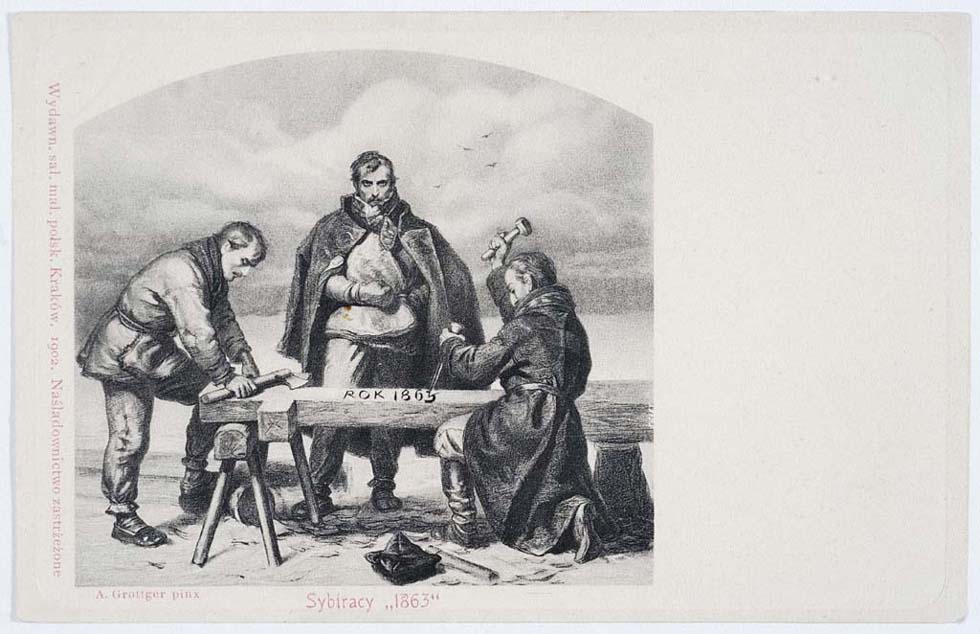

A photo of Poles and Polish Americans.

Do we look like scum to you?

If so, why?

On July 28, 2007, the Boston Globe published "Silence Lifts on

Poland's Jews," an essay by Rabbi Joseph Polak, Director of the Florence

and Chafetz Hillel House at Boston University.

Rabbi Polak's essay is now on the homepage of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

That is unfortunate.

Quickly after its 2007 appearance in the Boston Globe, a fan cut and pasted Rabbi Polak's essay to another website, with a new title. The new title was "Polish Scum."

Rabbi Polak, in "Silence Lifts on Poland's Jews," exploits the brute Polak stereotype that "Bieganski" exposes and critiques.

Rabbi Polak's essay begins with his equation of Poland with the murder of Jews. Poland has no other identity in Rabbi Polak's essay.

Jews, Rabbi Polak reports, "were brought there to be murdered." Note Rabbi Polak's use of the passive voice. Had Rabbi Polak used the active voice, he would have had to identify who brought Jews to Poland to be murdered. Rewrite Rabbi Polak's opening sentence in the active voice: "German Nazis brought Jews to occupied Poland to murder them."

That is a very different sentence.

Provide a key detail: "German Nazis brought Jews to occupied Poland to murder them in concentration camps that included Polish prisoners and Polish victims."

With the inclusion of that key detail in the opening sentence, the entire essay becomes a different essay.

In Rabbi Polak's lengthy essay, Germans are mentioned, once, in passing, in the third paragraph. What did these Germans do? They offered "a little help" to Poles in murdering Jews.

In Rabbi Polak's worldview, now sanctioned by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Germans didn't build Auschwitz to incarcerate, torture and murder Poles, eighteen months before its dedication to Jewish victims – although, in historical fact, they did. Germans didn't kill Poles for helping Jews – again, they actually did. Germans didn't commit what historian Michael Phayer called a genocide of Polish Catholics, before they got down to the genocide of the Jews. But they did. In Rabbi Polak's essay, none of that happened. Rabbi Polak's selective focus contributes to his depiction of Poles as scum.

Rabbi Polak allows that, in 2007, after his visit, "Poles are finally beginning to deal with these ghosts in their midst."

Rabbi Polak's word choices locate essentially anti-Semitic Poland, languishing in the past, and contrast that Poland with the future, and modern, evolved persons like himself and other non-Poles, who visit Poland and teach Poles about their debased state.

Thanks to visits like his, Rabbi Polak reports, Poles are learning to be "thoughtful." They are learning to be "truthful." Poland is "turning a corner," an American expression meaning to begin a new direction. Before the arrival of Rabbi Polak and others like him, not thought and truth, but stupidity and lies, had constituted the Polish character.

Poland, foolishly, saw itself as a "victim among victims" of Nazi aggression.

In fact, Rabbi Polak and other disseminators of the brute Polak stereotype are the ones who falsify history. Poland very much was a "victim among victims." To deny Nazism's, and communism's goals and crimes against Poland is tantamount to Holocaust denial.

Rabbi Polak's essay is now on the homepage of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

That is unfortunate.

Quickly after its 2007 appearance in the Boston Globe, a fan cut and pasted Rabbi Polak's essay to another website, with a new title. The new title was "Polish Scum."

Rabbi Polak, in "Silence Lifts on Poland's Jews," exploits the brute Polak stereotype that "Bieganski" exposes and critiques.

Rabbi Polak's essay begins with his equation of Poland with the murder of Jews. Poland has no other identity in Rabbi Polak's essay.

Jews, Rabbi Polak reports, "were brought there to be murdered." Note Rabbi Polak's use of the passive voice. Had Rabbi Polak used the active voice, he would have had to identify who brought Jews to Poland to be murdered. Rewrite Rabbi Polak's opening sentence in the active voice: "German Nazis brought Jews to occupied Poland to murder them."

That is a very different sentence.

Provide a key detail: "German Nazis brought Jews to occupied Poland to murder them in concentration camps that included Polish prisoners and Polish victims."

With the inclusion of that key detail in the opening sentence, the entire essay becomes a different essay.

In Rabbi Polak's lengthy essay, Germans are mentioned, once, in passing, in the third paragraph. What did these Germans do? They offered "a little help" to Poles in murdering Jews.

In Rabbi Polak's worldview, now sanctioned by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Germans didn't build Auschwitz to incarcerate, torture and murder Poles, eighteen months before its dedication to Jewish victims – although, in historical fact, they did. Germans didn't kill Poles for helping Jews – again, they actually did. Germans didn't commit what historian Michael Phayer called a genocide of Polish Catholics, before they got down to the genocide of the Jews. But they did. In Rabbi Polak's essay, none of that happened. Rabbi Polak's selective focus contributes to his depiction of Poles as scum.

Rabbi Polak allows that, in 2007, after his visit, "Poles are finally beginning to deal with these ghosts in their midst."

Rabbi Polak's word choices locate essentially anti-Semitic Poland, languishing in the past, and contrast that Poland with the future, and modern, evolved persons like himself and other non-Poles, who visit Poland and teach Poles about their debased state.

Thanks to visits like his, Rabbi Polak reports, Poles are learning to be "thoughtful." They are learning to be "truthful." Poland is "turning a corner," an American expression meaning to begin a new direction. Before the arrival of Rabbi Polak and others like him, not thought and truth, but stupidity and lies, had constituted the Polish character.

Poland, foolishly, saw itself as a "victim among victims" of Nazi aggression.

In fact, Rabbi Polak and other disseminators of the brute Polak stereotype are the ones who falsify history. Poland very much was a "victim among victims." To deny Nazism's, and communism's goals and crimes against Poland is tantamount to Holocaust denial.

Warsaw, 1945 source

Poland, Rabbi Polak reports, never referred to its Jews;

Poland was silent. Again, this is false. Poles very much did address the

Holocaust before the arrival of Rabbi Polak; this is recorded in English-language

books that Rabbi Polak could and should have cited, including several volumes

of "Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry" and "Bondage to the Dead."

It is true that public discourse about anything and everything was deeply distorted and truncated under the Communists. This distortion of public discourse was proverbial and all-pervasive. Public discourse was corrupted around everything from Soviet economics – "We pretend to work and they pretend to pay us" – to the chronic shortage of feminine hygiene products. A government that penalizes citizens for mentioning consumer-goods shortages is not going to allow vigorous discussion of the Holocaust.

Though not hampered by Soviet oppression, American and Israeli Jews also long-delayed their own response to the Holocaust. As Peter Novick, Jerzy Kosinski and Tom Segev have pointed out, there was measurably more attention paid to the Holocaust in America and Israel generations after WW II ended than during the war itself.

Even so, even under impossible conditions, Poles managed to publish essays, poetry, and broadsides, and to make films. Poles like Czeslaw Milosz, Jerzy Ficowski, Jan Blonski, Marcel Lozinski and Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, and institutions like the Jagiellonian University, took up the issue of the Holocaust and Polish culpability when it was risky to do so. Even simple Polish wood carvers chose to commemorate Poland's lost Jews in their carvings, and announced that they did so to rescue the memory of their lost Jewish neighbors.

Jerzy Kosinski visited Poland, his birthplace, long before Rabbi Polak got there. In 1988, he published an essay about his experience. He wrote that returning to Poland after many years away, he was eagerly received by young people. "With so much Jewish cultural legacy steaming from the spiritually fertile Polish soil, to these young men and women Polish-Jewish relations are a mystery – mystery, not stigmata. They are as prompted to know me better as I am eager to know them." This process was a mutually fruitful exchange, Kosinski reported. He reported that he was so "rejuvenated by what I found within myself during my twelve days in Poland [that] I started a new romance with my thousand-year-old, Polish-Jewish soul."

Rabbi Polak says that Poland's treatment of Jews was a "mixed bag," that Poland made an effort, "centuries long, of preserving the Jews' otherness." This statement is bizarre. Jews enjoyed a great deal of autonomy in Poland. Leaders of the Jewish community used that autonomy to preserve Jews' otherness. Every historian working on Polish-Jewish relations agrees on this point. The average Boston Globe reader would not know that. Thus, Rabbi Polak gets away with saying something that is utterly contrary to the historical record – something that serves a racist stereotype.

Because Poles are themselves so unevolved, outsiders, modern, superior, non-Poles, must, as Rabbi Polak puts it, "make Poland itself cry for its murdered Jews."

No Pole, before Rabbi Polak and other superior, modern people arrived, has ever felt any sadness over the Holocaust. As Rabbi Polak puts it, visitors will ask, "Does anybody here miss them?" It will take outsiders to bring to Poles' attention that they haven't the emotional depth to miss or to mourn Poland's murdered Jews. Again, these non-Polish visitors will force upon debased Poles a key question: "Why Poland did so little to save" its Jews.

Why did Poland do so little to save Jews? Rabbi Polak leaves the question a rhetorical one. He never attempts to answer it. Answers are complicated, of course. One quick and easy answer is the conditions of Nazi occupation in Poland. This catastrophic, genocidal occupation is a bagatelle to Rabbi Polak. Poland murdered its Jews, Rabbi Polak says, "with a little help from Germans," mentioning the Germans only once, in passing, in his lengthy essay. Poland and the Poles' debased essence are fully responsible for the Holocaust. As Rabbi Polak puts it, "death oozes everywhere from its [Poland's] pores."

After I read Rabbi Polak's piece in 2007, I was troubled. How to describe, in a short essay that the Boston Globe might consider publishing, in fewer than one thousand words, all that was misleading, racist, and harmful in Rabbi Polak's piece? How to present deeply complicated truths?

I wrote the piece, below, and sent it to the Boston Globe and the rabbi himself. Weeks went by. I received no reply from the Boston Globe. I resubmitted and received a form rejection.

***

It is true that public discourse about anything and everything was deeply distorted and truncated under the Communists. This distortion of public discourse was proverbial and all-pervasive. Public discourse was corrupted around everything from Soviet economics – "We pretend to work and they pretend to pay us" – to the chronic shortage of feminine hygiene products. A government that penalizes citizens for mentioning consumer-goods shortages is not going to allow vigorous discussion of the Holocaust.

Though not hampered by Soviet oppression, American and Israeli Jews also long-delayed their own response to the Holocaust. As Peter Novick, Jerzy Kosinski and Tom Segev have pointed out, there was measurably more attention paid to the Holocaust in America and Israel generations after WW II ended than during the war itself.

Even so, even under impossible conditions, Poles managed to publish essays, poetry, and broadsides, and to make films. Poles like Czeslaw Milosz, Jerzy Ficowski, Jan Blonski, Marcel Lozinski and Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, and institutions like the Jagiellonian University, took up the issue of the Holocaust and Polish culpability when it was risky to do so. Even simple Polish wood carvers chose to commemorate Poland's lost Jews in their carvings, and announced that they did so to rescue the memory of their lost Jewish neighbors.

Jerzy Kosinski visited Poland, his birthplace, long before Rabbi Polak got there. In 1988, he published an essay about his experience. He wrote that returning to Poland after many years away, he was eagerly received by young people. "With so much Jewish cultural legacy steaming from the spiritually fertile Polish soil, to these young men and women Polish-Jewish relations are a mystery – mystery, not stigmata. They are as prompted to know me better as I am eager to know them." This process was a mutually fruitful exchange, Kosinski reported. He reported that he was so "rejuvenated by what I found within myself during my twelve days in Poland [that] I started a new romance with my thousand-year-old, Polish-Jewish soul."

Rabbi Polak says that Poland's treatment of Jews was a "mixed bag," that Poland made an effort, "centuries long, of preserving the Jews' otherness." This statement is bizarre. Jews enjoyed a great deal of autonomy in Poland. Leaders of the Jewish community used that autonomy to preserve Jews' otherness. Every historian working on Polish-Jewish relations agrees on this point. The average Boston Globe reader would not know that. Thus, Rabbi Polak gets away with saying something that is utterly contrary to the historical record – something that serves a racist stereotype.

Because Poles are themselves so unevolved, outsiders, modern, superior, non-Poles, must, as Rabbi Polak puts it, "make Poland itself cry for its murdered Jews."

No Pole, before Rabbi Polak and other superior, modern people arrived, has ever felt any sadness over the Holocaust. As Rabbi Polak puts it, visitors will ask, "Does anybody here miss them?" It will take outsiders to bring to Poles' attention that they haven't the emotional depth to miss or to mourn Poland's murdered Jews. Again, these non-Polish visitors will force upon debased Poles a key question: "Why Poland did so little to save" its Jews.

Why did Poland do so little to save Jews? Rabbi Polak leaves the question a rhetorical one. He never attempts to answer it. Answers are complicated, of course. One quick and easy answer is the conditions of Nazi occupation in Poland. This catastrophic, genocidal occupation is a bagatelle to Rabbi Polak. Poland murdered its Jews, Rabbi Polak says, "with a little help from Germans," mentioning the Germans only once, in passing, in his lengthy essay. Poland and the Poles' debased essence are fully responsible for the Holocaust. As Rabbi Polak puts it, "death oozes everywhere from its [Poland's] pores."

After I read Rabbi Polak's piece in 2007, I was troubled. How to describe, in a short essay that the Boston Globe might consider publishing, in fewer than one thousand words, all that was misleading, racist, and harmful in Rabbi Polak's piece? How to present deeply complicated truths?

I wrote the piece, below, and sent it to the Boston Globe and the rabbi himself. Weeks went by. I received no reply from the Boston Globe. I resubmitted and received a form rejection.

***

Below, please find my response to "Silence Lifts on Poland's Jews" submitted to, and rejected by the Boston Globe:

***

In 1941, Oswald

Rufeisen was walking along a street. A peasant passed on a horse cart. The

stranger gestured for Rufeisen to join him. "The Nazis are murdering Jews.

I will hide you." Rufeisen was incredulous; Germans were civilized. Who

was this Pole? Was this a trap? The Pole persisted. Rufeisen gave in. The Pole

saved Rufeisen's life.

In 1987, I was attending a Polish-Jewish conference. Our meetings roiled, like a summer thunderstorm. I had been debating all night with the son of a concentration camp survivor. We took a break around dawn, silently strolling Krakow's cobblestones. Viewing glistening dewdrops on a spider web, this young Canadian Jew, who had never before been to Poland, began to recite, in Polish, the poetry of national bard Adam Mickiewicz.

I study Polish-Jewish relations. In hell, one discovers diamonds unavailable in any other mine. One example: Stefania Podgorska, a Polish teenager who saved 13 Jews thanks to a disembodied voice that directed her to shelter.

I've read thousands of books, articles, and internet posts. I've met key historical figures. I've traveled to Poland and Israel. I've conducted hundreds of interviews. You think I'm about to say, "This qualifies me." Think again. The more I read, the more I am agog, the more I want to say, "I have no right to speak." Because, in the Polish-Jewish narrative, whipsawing plot twists never let up. One example: after the war, Podgorska was dismissed, by a Jew she saved, as an inferior and superfluous "goyka." So, I do speak, because mainstream media simplifies this narrative beyond recognition.

What I think I've learned is this: hate, all hate, is wrong; and human beings, including those we least suspect, shelter reservoirs of goodness and strength.

The years before World War Two were a perfect storm. A toxic cloud circled the globe. Scientific Racism, a perversion of Darwinism, pitted "races" in a struggle for survival of the fittest. American racists cited "evidence" that Poles and Jews, inter alia, were essentially unfit; their entry was barred in 1924. In England, Nazism's sympathizers included the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. In Poland, some nationalists, the Endeks, struggling against three occupying empires, rejected Poland's traditional tolerance, and adopted a Poland-for-Poles stance. World War I, the Russian Revolution, the Versailles Treaty, and the Depression set the stage for racism's most diabolical manifestation: Nazism.

Massive, bulky narratives – a thousand years of Polish-Jewish relations and the black hole of World War Two – are simplified by sound bite culture: Poles become essential anti-Semites; everyone else, including the British Royal Family and followers of Oswald Mosley and Churchill and Roosevelt who heard Jan Karski's report and did not act, the Ivy League universities, the New York Times, the Atlantic Monthly, that all supported Scientific Racism – everyone – is exculpated. The essential, brute Polak takes on everyone's guilt. Important voices like Adam Michnik and Ewa Hoffman have refuted this charge; some of their fellow Jews have criticized them for mending fences with Poles.

Not Poland's good name – neither vanity nor even honor – is the treasure at stake here. Read the primary documents of Scientific Racism. Gathering only enough "evidence" to explain our fellow human beings as essentially different is exactly racism's error.

We may convince ourselves that this or that anecdote proves that Poles are essentially anti-Semitic … that African Americans are essentially lazy … that Jews are … fill-in-the-blank.

That method of thought, that is so easy, that is slickly seductive, that rewards our synapses with the conviction that we've got it all figured out, is what we must resist. Not for the sake of the Poles. Not for the sake of the African Americans, the Muslims or the Jews. We must resist that form of thought for ourselves. We must retain our intellectual and spiritual integrity, in a world that tempts us to believe that human beings and entire nations can be divided between the good and the bad, with us, and our nation, always firmly in the former category.

If you asked me where I am, in my twenty years of study of Polish-Jewish relations, I would tell you that every time I crack a new book, every time I interview a new source, I take that proverbial journey-inaugurating first step; I see a new horizon. I can't enumerate here the facts that counter the sound bite of Poles as essential anti-Semites. I can, though, say that when you find some evidence that convinces you that your neighbor is something essentially other than yourself, that is exactly when you must begin to question.

***

When his "Polish Scum" essay first appeared, I emailed Rabbi Polak and informed him of my concerns. Other concerned Polonians did, as well. Rabbi Polak was intransigent; he reported no movement in this thoughts about Poles.

I have sent Rabbi Polak an e-mail informing him of this blog post, and invited him to respond. If Rabbi Polak does respond, I will post his entire response, unedited.

In 1987, I was attending a Polish-Jewish conference. Our meetings roiled, like a summer thunderstorm. I had been debating all night with the son of a concentration camp survivor. We took a break around dawn, silently strolling Krakow's cobblestones. Viewing glistening dewdrops on a spider web, this young Canadian Jew, who had never before been to Poland, began to recite, in Polish, the poetry of national bard Adam Mickiewicz.

I study Polish-Jewish relations. In hell, one discovers diamonds unavailable in any other mine. One example: Stefania Podgorska, a Polish teenager who saved 13 Jews thanks to a disembodied voice that directed her to shelter.

I've read thousands of books, articles, and internet posts. I've met key historical figures. I've traveled to Poland and Israel. I've conducted hundreds of interviews. You think I'm about to say, "This qualifies me." Think again. The more I read, the more I am agog, the more I want to say, "I have no right to speak." Because, in the Polish-Jewish narrative, whipsawing plot twists never let up. One example: after the war, Podgorska was dismissed, by a Jew she saved, as an inferior and superfluous "goyka." So, I do speak, because mainstream media simplifies this narrative beyond recognition.

What I think I've learned is this: hate, all hate, is wrong; and human beings, including those we least suspect, shelter reservoirs of goodness and strength.

The years before World War Two were a perfect storm. A toxic cloud circled the globe. Scientific Racism, a perversion of Darwinism, pitted "races" in a struggle for survival of the fittest. American racists cited "evidence" that Poles and Jews, inter alia, were essentially unfit; their entry was barred in 1924. In England, Nazism's sympathizers included the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. In Poland, some nationalists, the Endeks, struggling against three occupying empires, rejected Poland's traditional tolerance, and adopted a Poland-for-Poles stance. World War I, the Russian Revolution, the Versailles Treaty, and the Depression set the stage for racism's most diabolical manifestation: Nazism.

Massive, bulky narratives – a thousand years of Polish-Jewish relations and the black hole of World War Two – are simplified by sound bite culture: Poles become essential anti-Semites; everyone else, including the British Royal Family and followers of Oswald Mosley and Churchill and Roosevelt who heard Jan Karski's report and did not act, the Ivy League universities, the New York Times, the Atlantic Monthly, that all supported Scientific Racism – everyone – is exculpated. The essential, brute Polak takes on everyone's guilt. Important voices like Adam Michnik and Ewa Hoffman have refuted this charge; some of their fellow Jews have criticized them for mending fences with Poles.

Not Poland's good name – neither vanity nor even honor – is the treasure at stake here. Read the primary documents of Scientific Racism. Gathering only enough "evidence" to explain our fellow human beings as essentially different is exactly racism's error.

We may convince ourselves that this or that anecdote proves that Poles are essentially anti-Semitic … that African Americans are essentially lazy … that Jews are … fill-in-the-blank.

That method of thought, that is so easy, that is slickly seductive, that rewards our synapses with the conviction that we've got it all figured out, is what we must resist. Not for the sake of the Poles. Not for the sake of the African Americans, the Muslims or the Jews. We must resist that form of thought for ourselves. We must retain our intellectual and spiritual integrity, in a world that tempts us to believe that human beings and entire nations can be divided between the good and the bad, with us, and our nation, always firmly in the former category.

If you asked me where I am, in my twenty years of study of Polish-Jewish relations, I would tell you that every time I crack a new book, every time I interview a new source, I take that proverbial journey-inaugurating first step; I see a new horizon. I can't enumerate here the facts that counter the sound bite of Poles as essential anti-Semites. I can, though, say that when you find some evidence that convinces you that your neighbor is something essentially other than yourself, that is exactly when you must begin to question.

***

When his "Polish Scum" essay first appeared, I emailed Rabbi Polak and informed him of my concerns. Other concerned Polonians did, as well. Rabbi Polak was intransigent; he reported no movement in this thoughts about Poles.

I have sent Rabbi Polak an e-mail informing him of this blog post, and invited him to respond. If Rabbi Polak does respond, I will post his entire response, unedited.

.jpg)