Adolf Hitler was not World War Two's only genocidal monster. Joseph Stalin, America's ally, the man FDR called "Uncle Joe," and "a Christian gentleman" was also a mass murderer. Poles were not alone in their victimization at the hands of Stalin; there were also Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and others. I ask, why is it okay for a student to wear a t-shirt with a Soviet red star or other Soviet paraphernalia to class, while a Hitler t-shirt or SS paraphernalia is taboo? One reason is that elites, predominantly leftist, have underplayed Stalin's crimes. "Maps and Shadows" will help to bring a buried story to light, and deepen understanding of World War Two. Jopek's delicate poetry and prose will do the work that professional historians have failed to do.

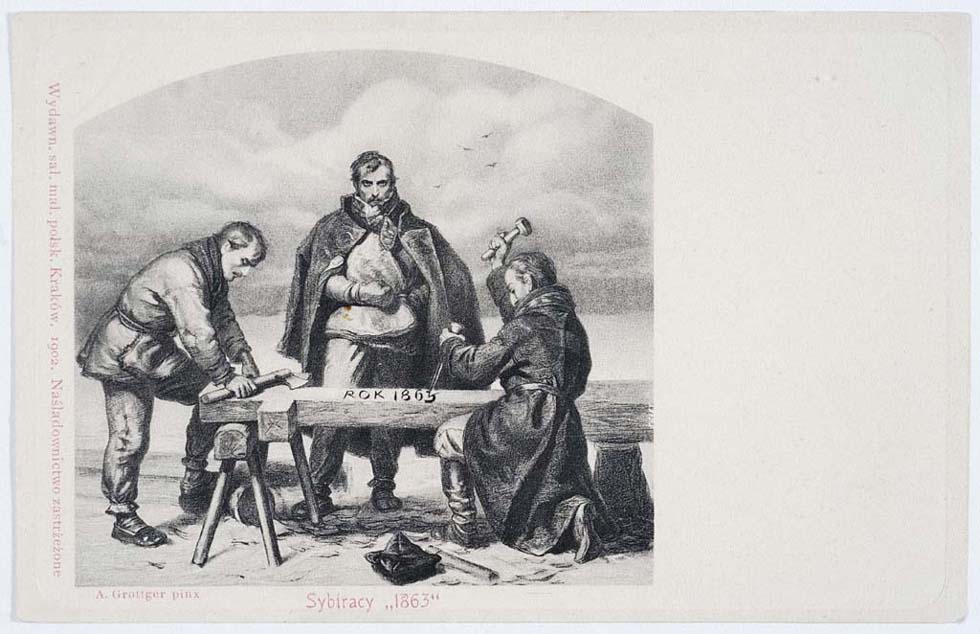

Hitler and Stalin both invaded Poland in September, 1939, thus igniting World War Two. Both vowed to destroy Poland and eliminate Poles. Stalin packed over a million Poles into cattle cars and deported them to Siberian labor camps, with the goal of working them to death. Forced to fell trees in freezing conditions, given inadequate calories, many died. In August, 1941, tens of thousands of Poles were released to fight in Anders Army, alongside the British. They fought with distinction, especially at Monte Cassino. Pawns in a vicious game, Poles survived on their own wits, in the cattle cars, in Siberia, in Iran, Italy, Africa, and England. Many died and were buried in unmarked graves, their fate known only by the carrion feeders who turned them to dust.

The opening chapter of "Maps and Shadows" is told in the words of Helen, or Helcia, the only girl in the family. The following chapter is told by Henry, or Henryk, Helen's younger brother. Other chapters are written in the voice of Andrzej, the father, and Zofia, the mother. Jopek's own poems are interspersed throughout the chapters. This style of storytelling works well. The family is split up, and mother and son, husband and wife, have no contact with each other, or even certain knowledge of each other's existence, for long stretches. Each family member gives voice to his or her own unique experience of exile. Henry focuses on the process of growing into manhood while in the Gulag and then as a young soldier, so starved he cannot hold up the uniform the Brits issue to him. Helen grows from a girl and an older sister to a teacher of other refugees.

The discontinuous storytelling style works for another reason, as well. People crave narrative structure: a beginning, a complication, action, resolution, and a happy ending. Atrocity does not respect human expectations. Atrocity violates humanity in every way. One way is this: it violates our order. This humble family, probably like the reader's own family, is rousted out of bed in the middle of the night by Soviet soldiers with guns, terrorized, humiliated, and dispossessed. The fleeting glimpse they have of their beloved home as they are packed off to a white hell is the last glimpse of home they will ever have.

There is no triumphant battle – only endless days in a cattle car with no toilet and scores of other deportees. Meaning is shattered. Normal time is meaningless. Father Andrzej and mother Zofia age decades in this one deportation, as they see on each other's faces. Destinations mean nothing – Helen is so ill in India she has no memory of India. People struggle to create meaning, routine, in chaos and injustice: Gulag internees gather mushrooms they don't immediately consume, in spite of hunger, but save for winter. Polish refugees in Africa name their little encampment and go to school, never knowing when or if they will be able to apply what they learn. Siberian refugees, inured to temperatures of forty below, are suddenly plunked down in Iran's unbearable heat; they go for a swim; one drowns in an utterly unfamiliar menace: a sandstorm. Other refugees die from the blessing of food. They had been in Siberia so long they could not digest British rations. Humiliations never stop: after the Poles connect with their British commanders, they are stripped naked and their possessions are burned. Their body hair is shaved off. Martyrdom is not always an apt study for an oil painting; martyrdom sometimes means traveling on a boat up to your ankles in others' vomit, watching your fellow passengers' corpses dumped overboard. Yet humanity remains, "Out of respect we didn't stare at the bodies." Those who manage to survive often don't know why. Helen was unconscious for weeks, the skin of her back worn away, and her vertebrae exposed. Yet she lived, while the healthy man who swam before a sandstorm did not. You stop asking why.

Jopek's writing is always stoic. The book is quick and can be read in one sitting. Readers should not be afraid to read this book. There are no lingering, detailed accounts of cruelty or torture. Jopek's tone is businesslike. This is what happened. Now, on to the next impossibility.

Poles and Poland are often misrepresented in popular, journalistic, and scholarly discourse. There are complicated reasons for that covered in my own book, Bieganski. Books like "Maps and Shadows" will deepen and broaden the reader's understanding of one of the most cataclysmic events in world history, World War Two.

Danusha, thanks for the review. I'm in the process of reading the book myself and have to agree with you that it's moving and important.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much for your blog and for highlighting 'Maps & Shadows' which I will immediately buy & read...... MUCH MORE information about us Poles needs to be spread so the world knows 'the truth'...... THANK YOU !

ReplyDeleteCzuwaj,

Krysia

New Jersey